This story is one of those curiosities, a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction kind of anecdote. I highlight it for that reason only…I see no greater symbolism here nor any type of divine intervention. Just a remarkable stroke of luck for the beleaguered United States.

The War of 1812 was a bizarre episode in U.S. History. Both nations went into the war with few clear objectives. Neither were prepared. The campaigns are a litany of tragic, botched efforts resulting in pointless bloodshed. And in the end, everything returning to status quo ante bellum, that is, as they were prior to the war.

It raises the question, “Why did we fight?” That large topic is not the subject of this post. I’ll simply say that the war clearly had more to do with western territory than anything else, setting up a pattern for all U.S. wars in the 19th century. The traditional interpretation which many of us were taught focuses on the issue of sovereignty on the high seas and the notion of the War of 1812 as the “Second War of Independence.” This misses the point. We had our independence. Our independence was not incomplete nor was it in jeopardy. If shipping rights were the issue then why did both nations devote so many resources to land campaigns focusing almost exclusively on our western frontier?

But, I digress. Back to the tornado.

By the summer of 1814, two years into the war, the United States was in trouble. There had been numerous bungled attempts to invade Canada (the objective seemingly to occupy what is now eastern Ontario…though I’m not sure that objective was ever really understood or articulated by American leaders). There had been a successful campaign under Major General William Henry Harrison in Canada, but unfortunately the War Department refused to fully support it. Harrison therefore gave his resignation and his success came to nothing.

Things got worse in April 1814. Great Britain, to our advantage, had been fighting two wars at once. But when Napoleon surrendered to the Russians and was exiled to Elba, the Napoleonic Wars had, for the time being, ended. Now Great Britain could devote tens of thousands of battle-hardened veterans to the war against the United States. Thus far, we had been fighting demoralized British troops stationed in Upper Canada, many of them eager to desert. Now, grizzled men who had served under Wellington and fought against Napoleon would be invading our shores. This was a very different type of soldier. With this influx of veterans, Great Britain would finally go on the offensive.

One of the first targets in August 1814 was primarily a psychological one. Many British officers were pushing for the burning of Washington D.C. There were certainly more important strategic objectives. But there was a desire to avenge the plundering that Americans had committed in York (now Toronto) and strike a massive blow to American morale.

Landing in Benedict, Maryland on August 19, 1814, a British force of roughly 5,000 men marched towards Washington. An American force of roughly 7,000 led by Brigadier General William Winder made a largely pathetic attempt to stop the British at the Battle of Bladensburg, Maryland on August 24. I hesitate to use that word because there was some courageous fighting there on the part of many Americans. But the battle was so poorly planned, the American forces so confused, it turned into an awful rout very quickly. And the road to Washington lay wide open to the British.

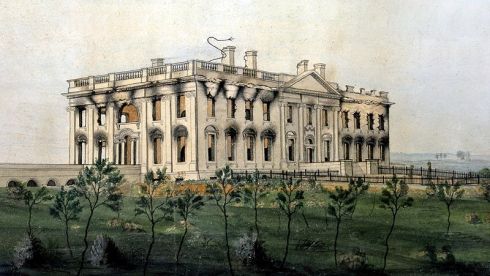

Once in Washington, the British burned the White House (after sitting down to eat a large feast that Dolly Madison and her staff had prepared for cabinet members before they were all forced to flee). The War Department, the State Department, the Treasury department and many other government offices were burned. And, of course, the Capitol building, with the original Library of Congress, was destroyed.

The policy was to leave private property alone. However, the conflagration of many public buildings threatened to spread out of control. The city was in jeopardy.

The next day, August 25, as fires still raged, a massive storm hit Washington. The driving rain put out most of the fires threatening the city. Perhaps more important, the invading British were so battered and demoralized, the storm played a large role in the decision to cut short the occupation of Washington.

The storm was so fierce that it tore buildings apart, literally lifting them off their foundations. The winds uprooted trees and knocked men to the ground. A number of houses collapsed, killing the British soldiers taking shelter therein. One British officer reported seeing cannons lifted off the ground and thrown through the air. Redcoats out on the streets of Washington, trying to enforce a curfew, were forced to lie prostrate in the mud.

Based on the first hand accounts, weather historians generally agree that the storm that struck Washington on August 25, 1814 sparked one or more tornadoes. I can’t possibly imagine being one of these soldiers, completely exposed, with no choice but to cling to mother earth in the midst of a tornado.

As the storm began to subside, one of the British officers in command of the invasion emerged from his shelter and said to one of the inhabitants of Washington, “Great God, Madam, is this the kind of storm to which you are accustomed in this infernal country?!”

She responded, “No, sir, this is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from the city.”

The quick-witted officer shot back, “Not so Madam. It is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.”

I have no opinion on Providence. But there can be no doubt that the tornado that struck Washington that day did more to save the capital than the United States Army ever did. The fires were largely extinguished. And the British limped back to their ships.

[Sources: A.J. Langguth, Union 1812, (2006), 308-311; Anthony S. Pitch, The Burning of Washington, (2000), 140-142.]

September 26th, 2016 at 2:55 am

I enjoyed your article on this however in reading other accounts of this incident they stated that the British ships were also heavily damaged by this storm.

October 17th, 2016 at 6:32 am

You omitted the British admiral’s response to the lady: “Not so Madam. It is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.”

October 17th, 2016 at 9:00 am

You’re right. And I think that’s worth adding in. Thanks for pointing it out.

July 20th, 2017 at 2:21 am

When was the last time a tornado hit Washington D.C. coincidence no, this was an act of God.

July 20th, 2017 at 6:41 am

A tornado hit Washington this year on April 6, 2017.

November 23rd, 2017 at 6:52 am

[…] After the British set fire to Washington D.C. during the War Of 1812, a tornado appeared out of nowhere and put out the fire saving Washington D.C.. Ref: historicaldigression.com/2012/03/26/a-tornado-saves-washington-during-the-war-of-1812/ […]