Various states that were involved in the Civil War, North and South, long ago placed their official monuments on various battlefields. Most chose to build their monuments at Gettysburg. It was, after all, the largest battle of the Civil War…in fact the largest battle ever fought in the western hemisphere…and one of crucial importance. So, Gettysburg was a logical choice.

There are more than a dozen state monuments on the Gettysburg Battlefield. These include the Virginia monument featuring bronze depictions of Virginian soldiers and a mounted Robert E. Lee sculpted by Frederick William Sievers, completed in 1913. And the colossal Pennsylvania monument, fittingly the largest of the monuments on the battlefield. Situated in the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, it is an imposing 110 feet tall, a building designed by architect W. Liance Cotrell with sculptures by Samuel A. Murray, completed in 1913.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts did not place a state monument at Gettysburg. The focus instead was on the Antietam Battlefield in Sharpsburg, Maryland. Antietam was, as is often quoted, the bloodiest single day in American history. It seems likely that Antietam was selected for a monument rather than Gettysburg due to the fact that a larger number of Massachusetts casualties were suffered during Antietam. There were also a great many Massachusetts leaders and units which played a significant role in the battle. Major General Joseph Hooker, for instance, commanded the I Corps which commenced the battle with an assault at 5:30 a.m. on the Confederate left flank near the Dunker Church. Roughly 8,000 men under Hooker’s command struggled through hellish fire in the infamous Cornfield and the East Woods. Another key commander, Major General Edwin Sumner of Massachusetts, led the II Corps. Sadly, his divisions were cut to pieces in the East Woods and in front of the Bloody Lane.

Perhaps the harrowing experience of the 12th Massachusetts Infantry is all that was needed to justify a Massachusetts State Monument at Antietam. As Hooker’s early morning assault fell apart, General Stonewall Jackson launched a counterattack. The 12th Massachusetts was one of the units that stood in the way of this onslaught. Standing toe to toe with the Louisiana Tigers in the Cornfield for some time, the 12th Massachusetts soon had to retreat under terrific fire. The 12th Mass suffered the worst casualties of any Federal unit on the field that day. Of the 334 that went into battle, 224 were killed, wounded or missing…a casualty rate of 67%. Some accounts give even higher casualty rates. When the 12th Mass regrouped in the North Woods, only 32 men were standing to rally around the colors.

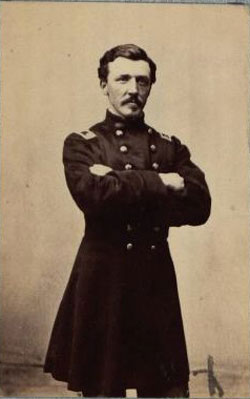

Lt. Col. Wilder Dwight (1833-1862), of the 2nd Massachusetts, fell mortally wounded on the spot where the Massachusetts monument at Antietam is now located.

And then there was the advance of the 2nd Massachusetts through the Cornfield. The unit had suffered roughly 35% casualties just over a month prior at the Battle of Cedar Mountain. Second in command of the unit was Lt. Col. Wilder Dwight, a 29 year-old lawyer from Brookline–charismatic, much admired by his men, he seemed to have potential and Massachusetts newspapers paid attention to his actions. Pressing forward to within sight of the Dunker Church, the 2nd Massachusetts soon found that the units on either side of them had fallen back. They were isolated with a solid force of Confederates in their front behind stone walls and fences. This advance is depicted at the beginning of the film “Glory.” In this position, a quarter of the unit fell, including Lt. Col. Dwight, shot once in the hip and again in the wrist. He was mortally wounded. Soldiers tried to remove him from the field but he refused due to the pain. As the 2nd Massachusetts retreated, Dwight took out a letter he had been writing earlier that morning to his mother. At the foot, he added, “I am wounded so as to be helpless. Good by, if so it must be. I think I die in victory. God defend our country. I trust in God, and love you all to the last. Our troops have left the part of the field where I lay.” Dwight died two days later in a field hospital.

The Massachusetts monument at Antietam is located on the spot where Lt. Col. Wilder Dwight fell. The piece of ground, now part of Antietam National Battlefield Park, was bought by the Commonwealth for the express purpose of building a monument in the 1890s. The monument, designed by the Boston architectural firm of Winslow & Wetherell, was dedicated on September 17, 1898. A large delegation of Massachusetts dignitaries were present for the event. The key note address was given by Governor Roger Wolcott of Massachusetts.

The New York Times described the monument as “exceedingly simple and chaste in design.” Indeed, many have thought it was intended as an enormous pedestal for a statue that was never placed. It was, however, designed to be reminiscent of sarcophagus and, in my opinion, needs no further adornment.

October 19th, 2016 at 4:12 pm

From a Google search I found your blog. Great information!

I have over 130 letters written by my great-grandfather, Francis A. Bliss, during the Civil War. He enlisted into the cavalry (1st Mass. Regiment, Co. I) in Oct., 1861 from Rehoboth. His and my ancestry goes back to an emigration in 1636 from England with a settling in Rehoboth in 1644. Our family still owns the original homestead.

Fortunately his was a prolific writer and had a very nice sister Rebecca who saved his letters. We also have a few original letters, wills, journals from the early 1800’s. The Civil War letters were transcribed by an avid historian from Rehoboth about 20 years ago. He left one copy of the transcription with my father, one for himself and another copy is in the Carpenter Museum in Rehoboth. I came across the transcription and located all the original letters. I am in the beginning process of creating a book of the letters with a sketch history of the family and of Rehoboth. I have a long way to go but I think it will be interesting history. I recently handed down Francis’ Spencer carbine, ammunition cases and saber to my son. Before doing so I photographed all of them for the book. They were given to me by my great-uncle years ago.

Unlike many of the other companies of the 1st Regiment, Francis spent much of the war in S.C., specifically, Hilton Head, Beaufort, and Port Royal. After that he was involved in the Battle of Olustee in FL. At that time i believe the unit was called the “Independent Battalion”. In March and April of 1864 his letters were written from Florida. In June of 1864 the letters were from Bermuda Hundred and other areas near Richmond and Petersburg. I understand that his Co. was in Appomattox at the end.

I have a few documents to rely on to do some researching. First I have a complete published genealogy of our family (3 huge volumes that was complete in 1981) and a book published in 1918 called “The History of Rehoboth” that includes Civil War information on soldiers including my great-grandfather and others that Francis knew and served with from town. His brother enlisted as a “nine-month man” and died of typhoid fever near New Orleans (Brashear City) before the siege of Port Hudson. Thomas’ Rehoboth friend Isaac Carpenter wrote back home of Thomas’ death. He was with him when he died.

Online I have also found “A History of the First Regiment of the Mass. Cavalry Volunteers”.

I’d be happy to share these letters and other information if you’d like. I have done a couple of things with the original transcription. First I scanned the non-digital pages into 2 pdf files. Secondly I have completed a scan and OCR on all the transcribed letters so they are now individual documents that can be edited, text reformatted, and copied and pasted into a book-style document. My wife and I are in the process of going through the letters and making corrections where we see errors. (I can’t imagine the task of transcribing them all originally and can understand why it took Mr. Dyer two years to get them done.)

If you have other suggestions for resources and reference materials that might help me I’d appreciate any assistance.

Regards,

David Bliss

January 26th, 2018 at 3:22 pm

I live on the farm near Keedysville, MD where Lt. Col. Wilder Dwight died after he was removed from the battlefield at Antietam. The farmhouse still stands where he died in 1862. We believe that house was built in 1850.