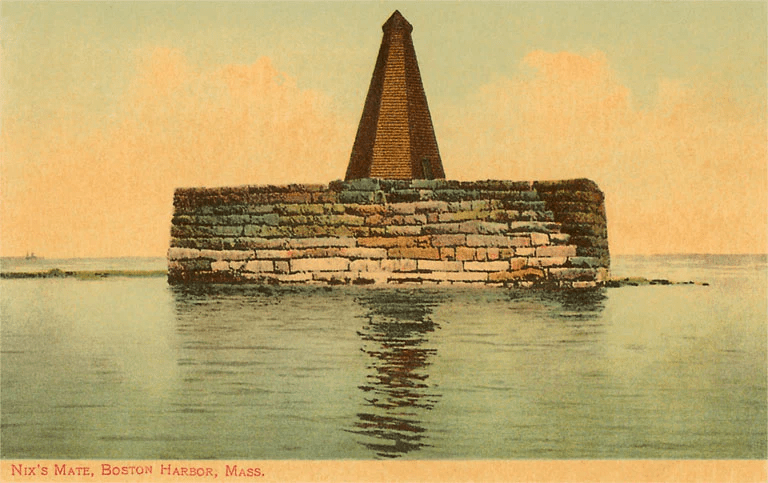

There’s a small island in Boston Harbor, shaped like a backward question mark, with the mysterious name of Nix’s Mate. It has a grim history. Positioned alongside the main harbor channel, where ships have entered and exited for centuries, the rocky shoals of Nix’s Mate—mostly hidden except at low tide—have ensnared many vessels over the years. The hazard was so severe that, in 1805, the Boston Marine Society constructed a massive granite pedestal there, 40 feet on each side and 16 feet tall, topped with a 20-foot pyramidal tower to serve as a “day beacon” (a non-illuminated guide).

Those who gaze upon it might not realize that the island, its history, and its alleged curse are all entwined with tales of pirates, murder, hangings—even witches and blood sacrifices. Some of these stories are true…others, not so much. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Let’s go back to July 25, 1851, when Henry David Thoreau was enjoying a ferry trip from Hingham to Hull on his way to Cape Cod. As they came within sight of the forlorn Nix’s Mate, Thoreau noticed a young boy on board, captivating a group of girls with a vivid tale. The boy recounted the old legend of a condemned man—a pirate who had allegedly plotted mutiny and murdered one Captain Nix. The mate sought to seize the captaincy for himself, but instead, when they made port in Boston, he was arrested, put on trial for piracy and murder, and sentenced to die a slow death, marooned on a small, barren island. According to the boy, Nix’s mate stood on the desolate shore, cursing his condemners, asserting his innocence as they rowed away, declaring, “If I am guilty, this island will remain, but if I am innocent, it will be washed away.” Thoreau noted the boy’s conviction as he gestured toward the eroding remains, remarking, “and now it is all washed away!” Fascinated, Thoreau jotted down a description of the moment.[1]

This story, typically recounted in similar fashion, was widely popular around Boston Harbor in the early 19th century. In some versions, Nix’s mate was executed and buried on the island rather than marooned, yet all versions agree on the presence of a curse—one that apparently came to fruition. By the early 1800s, the island had dwindled to a mere pile of rocks, barely above the waterline. An 1826 article, widely reprinted at the time, recounts an aged gentleman informing the writer that he remembered when Nix’s Mate was “verdant stand, on which a large number of sheep were pastured.”[2] In the 17th century, it was said to encompass about 12 acres.[3] Many have taken the island’s gradual disappearance as a sign of the mate’s innocence.

Perhaps the most baffling and broadly embellished version of the story appeared in an 1839 novel by Rufus Dawes entitled Nix’s Mate, an Historical Romance of America. In this retelling, Edward Fitzvassal, a brooding hero, leads a mutiny, setting Captain Nix adrift. Taking Nix’s identity, Fitzvassal arrives in Boston amid the 1689 Boston Revolt and heroically aids the colonists against the rule of King James II. His fate turns when the real Captain Nix reappears, leading to Fitzvassal’s conviction for piracy. Though pardoned for his service to the colony, Fitzvassal tragically takes poison before learning of his reprieve. He is buried on “Green Island,” which was thence after cursed by a Native American woman who loved him and in time the island washed away, becoming Nix’s Mate.

Interspersed in all this are inexplicable scenes of witches conducting black magic. As one literary historian put it, “For the most part it is a wild, disordered extravaganza. There is one scene, meant to be lurid, of witches drinking hot human blood in a cavern at Nahant!”[4] An unimpressed reviewer in 1839 wrote, “The whole passage of the midnight meeting [of witches] near Spouting Horn is disgusting.”[5] The book was adapted into a play in 1848 that starred Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., an older brother of John Wilkes Booth. So, during Thoreau’s time, the story had some traction.

Any basis in reality? Some. For that, we have to look back to a 1726 account by Cotton Mather. Perhaps the most influential Puritan minister, theologian, and author in New England in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Mather was pastor of Boston’s North Church. In his pamphlet, “The Vial Poured Out Upon the Sea” he recounts the fate of a group of convicted pirates, including the defiant Captain William Fly, brought in to Boston for execution. Fly and his fellow conspirators had murdered their captain and his mate. Ministers of the city, led by Mather, made great efforts to elicit repentance from the condemned men before they were hanged. While his companions repented, Fly stubbornly argued with Mather, denying guilt and rejecting his pleas to turn to God.[6]

The account is unexpectedly humorous. Mather seemed intent on capturing Fly’s insolence and depravity, yet to a modern reader, Fly’s snark and rejection of authority come across as oddly compelling. One might even wonder if Fly inspired the character of Captain Jack Sparrow, as he faced his execution with a comic flair, holding a nosegay and complimenting the crowd as he walked down the street. When he mounted the gallows, he even adjusted his own noose, admonishing the executioner for being poor at his trade.

Fly’s companions were buried on Nix’s Mate, but due to his refusal to repent, Fly’s body was displayed in a gibbet—an iron cage—left for passing crews to see as a deterrent to piracy. There are unverified accounts of other convicted pirates also being buried on Nix’s Mate, leading mariners and fishermen to see the island as a foreboding, perhaps cursed, place. According to one journalist, a ship captain used to insist that his crew doff their caps when passing the island.[7]

So there is indeed truth behind the island’s connection to the execution of pirates and their ignominious burial there. But as for the curse that caused the island to disappear into the sea…likely just a matter of erosion. Exacerbated by the fact that the island was a popular spot for crews to collect large volumes of stones for ballast to stabilize their vessels. There are numerous warnings against this practice on Nix’s Mate published by Boston authorities. One can imagine how this sort of activity would accelerate erosion.[8]

So there are some explanations rooted in truth that account for the island’s mysterious reputation. But that name—there is no explanation for it. In 18th century newspapers, various mentions of vessels gone aground there refer to the island as “Nick’s Mate.” My own theory? Nick was a common appellation in old New England for the Devil, and with the island’s reputation for dooming so many vessels in Boston Harbor, it may have become known among seafarers as the Devil’s first mate.

[1] Henry David Thoreau, Cape Cod, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 210.

[2] “Islands in Boston Harbor,” The Boston New-Letter and City Record, Saturday, December 16, 1826.

[3] John Winthrop, The History of New England, ed. James Savage (Boston: Phelps & Farnum, 1825), 154.

[4] Lindsay Swift, “Boston as Portrayed in Fiction,” The Book Buyer, October 1901, p. 199.

[5] “Nix’s Mate, Review.” Weekly Messenger, November 13, 1839, 4.

[6] Cotton Mather, The vial poured out upon the sea. A remarkable relation of certain pirates, etc… (Boston: T. Fleet, for N. Belknap, 1726).

[7] Auburn Daily Bulletin (New York), September 4, 1875, 4.

[8] Columbian Centinel (Boston), March 9, 1816.