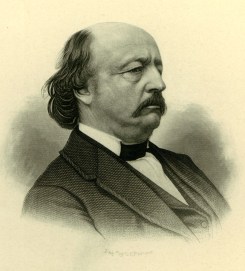

John Albion Andrew, from frontispiece of “A History of Massachusetts in the Civil War” by William Schouler, 1868

John Albion Andrew, the “War Governor” of Massachusetts, and President Abraham Lincoln had a thorny relationship. Fundamentally, the two stood for the same things. But they were polar opposites in personality and in their political tactics. This led to considerable frustration and drama.

Historian Allan Nevins described Andrew as “an aggressive, generous, choleric little man, the Miles Standish of the Bay State…far-sighted, fearless and unwearied…emotional and impulsive; he was tactless, and his fierce bluntness made many enemies…”[1] The description, if a little unforgiving, is not inaccurate.

While Andrew was aggressive, fiercely principled, energetic to a fault, Lincoln was patient and carefully deliberate. It was this difference in character more than any politics that led to problems.

The way in which they first met might offer something of a microcosm of their relationship to come. As far as I have been able to determine, Andrew first met Abraham Lincoln shortly after the Republication National Convention in May of 1860. During that convention, Andrew had played a significant role in swinging New England delegates away from Seward and towards Lincoln.

Lincoln was not at the convention—it was customary at that time for candidates to stay away from such things. But the newly nominated Republican candidate hosted the delegates at a massive reception a few days later in his Springfield home. John Andrew then met and shook hands with Lincoln, saying to him, “We claim you, Mr. Lincoln, as coming from Massachusetts, because all the old Lincoln name are from Plymouth County.” Lincoln replied, “We’ll consider it so this evening.”[2]

This was typical of their relationship: Andrew trying to “lay claim” to Lincoln in one way or another—on behalf Massachusetts, on behalf of the North, on behalf of the Radical Republicans, pushing him to move faster, more boldly. And Lincoln artfully accommodating Andrew, in some ways, and in others resisting him.

In an earlier article, I described the ways in which John Andrew energetically prepared for a war he knew was coming. It was no accident that when Lincoln called for troops, the 6th Massachusetts was the first volunteer unit to reach Washington. Lincoln, while inspecting their ranks on the White House lawn, said to the Massachusetts men, “I don’t believe there is any North…You are the only northern realities.” Lincoln was grateful and complimentary regarding the Bay State’s preparedness. Unfortunately, by the end of the year, a wedge would be driven between Lincoln and Andrew, largely due to the interference of a third party.

Benjamin Butler, a lawyer and politician from Lowell, Massachusetts, had long held a senior position in the Massachusetts militia. He was also a pro-slavery Democrat who had supported Jefferson Davis prior to the war. When the War Department asked Governor Andrew to designate a candidate for a Major General from Massachusetts, he had little choice but to put forth Butler. He must have found it distasteful given their political differences.[3]

Gen. Benjamin Butler (1818-1893)

Matters grew worse in the fall of 1861 when Butler hatched a plan to recruit his own regiments in Massachusetts and appoint his own hand-picked officers. This was highly unorthodox. Regiments were formed through the state militia under the supervision of the Governor. Massachusetts officers could only be commissioned by the Governor. And here Butler was raising his own troops with the permission of the United States War Department. Worse, the men Butler had picked for officers were strongly opposed to abolition. Andrew dug in his heels and refused to commission them.

The resulting battle was bitter, ugly, and truly unfortunate. Volumes of letters and telegraphs were sent by Andrew and Butler to the War Department and to the President arguing their views. Ironically, Andrew’s view of non-interference was essentially a state’s rights argument and one that Lincoln had little sympathy for.

Eliza Andrew happened to visit Washington that fall of 1861 during the controversy. She attended a soiree escorted by a Massachusetts officer named Howe. Lincoln greeted them, saying, “Well, how does your husband and General Butler get on? Has the governor commissioned those men yet?” As Mrs. Andrew searched for a response, Howe replied that he had heard that Lincoln commissioned them. “No,” Lincoln said, “but I’m getting mad with the governor and Butler both.”[4]

The new Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, eventually summoned Andrew to Washington. In a meeting with Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Stanton had discussed the matter, saying, “If I could meet Governor Andrew under an umbrella at the corner of the street, we could settle that matter in five minutes, if he is the man I take him for.”[5] Sumner assured him that he was.

While in Washington, Andrew refused to attend a White House reception, writing to his wife that such celebrations were inappropriate during a war. But he did meet privately with Lincoln and Stanton. They struck a deal. Andrew would appoint Butler’s men, even the proslavery ones. And in the future no one but the governor would appoint any officers or establish new regiments.

While the episode may have reached a satisfactory conclusion, most unfortunately, it made Andrew and Lincoln suspicious of one another for the remainder of the war. And Andrew would continue to press Lincoln to be ever more aggressive, insisting that military matters be executed faster. He had no patience for General George McClellan. And he was particularly unrelenting on the matter of emancipation.

A number of abolitionist Union generals had attempted to issue military orders freeing slaves within their regions of control only to be overridden by Lincoln. One of them, General David Hunter in command of the Department of South, which included the states of Georgia, South Carolina and Florida, freed slaves in those states with an order in May 1862. Lincoln immediately rescinded the order insisting, correctly, that such a measure could come only from the President.

Andrew attempted to argue with the administration, writing to Stanton, “If the President will sustain General Hunter, recognize all men, even black men, as legally capable of that loyalty the blacks are willing to manifest, and let them fight, with God and human nature on their side, the roads will swarm, if need be, with multitudes who New England would pour out to obey your call.”[6]

Only a few people knew that Lincoln was methodically working his way towards the Emancipation Proclamation during the summer of 1862. But he was adamant that the executive action had to stand on proper legal ground and that enough support be built up prior to issuing the order. These painstaking political matters were simply irrelevant to an agitator like Andrew.

His patience gone, Andrew began to publicly criticize Lincoln’s failure to take action on emancipation. He arranged a conference of New England governors which met in Providence in August 1862. There, the governors backed New England’s “War Minister” in their support of an immediate emancipation measure.

Thus bolstered, Governor Andrew called for a national conference of governors which was scheduled for September 24, 1862 in Altoona, Pennsylvania. Governor Andrew wrote to a friend, “I am sadly but firmly trying to organize some movement, if possible, to save the president from the infamy of ruining the country.”[7] This was the degree of urgency with which Andrew viewed emancipation and recruitment of black soldiers. If these measures were not immediately taken, he felt, the war would be lost. And given the way things were going at that time in the field, he had good reason to feel so.

As he was en route to the Altoona Conference, Governor Andrew learned of the release of the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln had pulled the rug out from under the governors. The Altoona conference, which probably would have urged an Emancipation Proclamation and perhaps even demanded McClellan’s removal now had little to do but simply draft a bland resolution congratulating Lincoln on the proclamation.

President Abraham Lincoln

Emancipation was a momentous step but Andrew was still not satisfied. He began to press the Massachusetts Congressional delegation to push through a constitutional amendment that would make emancipation permanent and not just a temporary war measure. Calling the Emancipation Proclamation a poor document but a mighty act, Andrew wrote to one of his aides, “Our Republicans must make it their business to sustain this act of Lincoln…No bickerings, no verbal criticism, no doubting Thomases must halt the conquering march of triumphant liberty…Tell Claflin, Sumner, Wilson, etc., to strike quick. Now, NOW, NOW!”[8] Despite Andrew’s urging, it would be another two and half years before Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery.

Andrew would continue to apply pressure on the federal government and there would be additional flares of temper between him and Lincoln. Andrew was particularly worried, towards the end of the war, that Lincoln would be swayed by peace Democrats who advocated letting the South go or encouraged its return with slavery intact.

In actuality, Andrew had little to fear when it came to Lincoln. The President accomplished virtually all that the hot-tempered governor had agitated for but on his on terms on in his own time. The two ended up in the same place politically, even if they had been distanced by personality.

And in the end, I think Governor Andrew understood this. Addressing the legislature after Lincoln’s assassination, the Governor expounded in elaborate language about Lincoln’s many virtues. But then he spoke more plainly, perhaps acknowledging the drawbacks of his own methods.

“The purpose of his mind,” Andrew said, “waited for the instruction of his deliberate judgment; and he was never ashamed to hesitate, until he was sure that it was intelligently formed…he was of so honest an intellect that by the processes of methodical reasoning he was often led so directly to his result that he occasionally seemed to rise into that peculiar sphere which we assign to those who, by original constitution, are natural leaders among men.”[9]

[1] The Lehrman Institute, “Abraham Lincoln and Massachusetts”

[2] William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1948), 62.

[3] Henry Greenleaf Pearson, The life of John A. Andrew, governor of Massachusetts, 1861-1865. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1904), 183.

[4] Hesseltine, 190.

[5] Pearson, 305.

[6] Albert G. Browne, Sketch of the official life of John A. Andrew, (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1868), 71.

[7] Hesseltine, 253.

[8] Browne, 74.

[9] Address of Governor John A. Andrew, Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the year 1865, (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1865), 811.