The Union soldiers gathered around Wilmer McLean’s house on the afternoon of April 9, 1865, stood in silence, sensing the gravity of the moment. They waited, men from many different units and from different states across the North as, inside, General Robert E. Lee signed the terms of surrender that would end the Army of Northern Virginia’s fight, an act that would eventually come to be regarded as the end of the war itself.

The front door opened. Lee, in his finest uniform, walked down the front steps, mounted his horse and began the short ride back to his lines to tell his soldiers that it was time to lay down their arms and go home. A moment later, Grant emerged. His boots and trousers were caked with mud from days of campaigning, and, in stark contrast to Lee, he wore an ill-fitting private’s uniform, having paid little attention to his appearance. As the news quickly spread, men in camps nearby began to cheer. Somewhere a battery began to thunder in salute.

Grant ordered it stopped immediately. There was to be no cheering, no demonstrations, no hundred gun salutes. Grant later wrote that he gave the order because he did not want his army to “exult” over the Confederates’ downfall.[1]

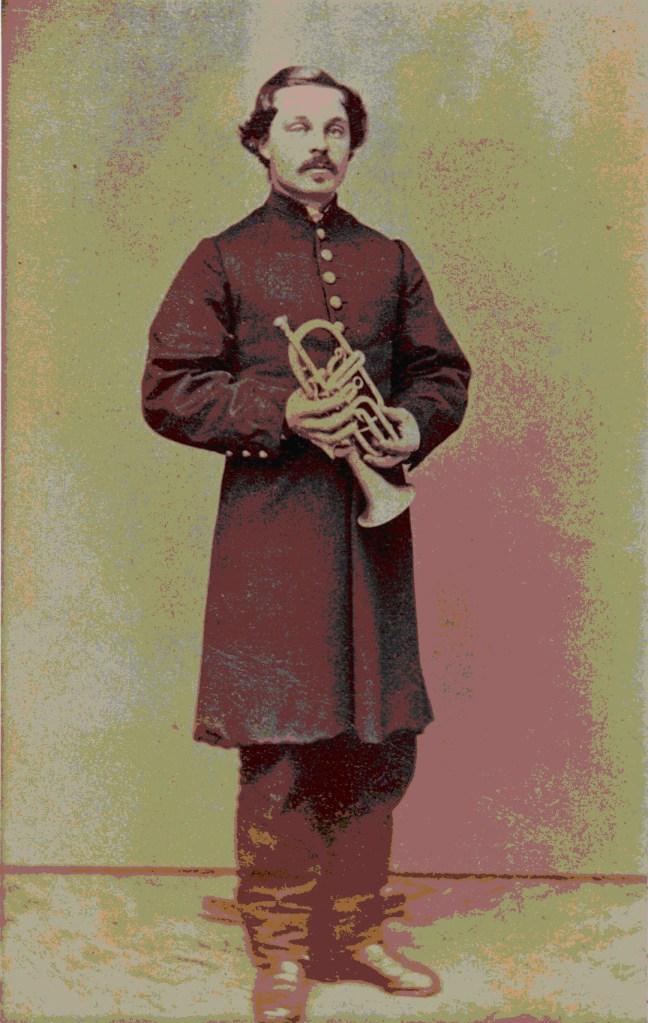

So, for a spell, a silence prevailed at Appomattox Court House. Then, unexpectedly, the stillness was broken. Softly at first, the regimental band of the 198th Pennsylvania began to play a tune, melancholy and familiar to all. It was “Auld Lang Syne.” It began spontaneously. One by one, the musicians joined in to play their parts. Among them was a young German immigrant named Justus Altmiller, who lifted his cornet and carried the melody, his clear notes capturing the poignancy of the moment.[2]

The Scottish song, with its well-known themes of farewell and remembrance, was an appropriate, but at the same time, a striking choice. So many regimental histories mention bands playing this song during the war, or soldiers singing it in camp. Along with “Home Sweet Home,” it was one of those tunes that reminded the soldiers of hearth, family, and all those they had left behind. It reminded them so acutely of home, in fact, that in December 1862 the song was forbidden in Union camps. The Army of the Potomac had just suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862 and morale was so low that officers resorted to desperate measures to curtail desertions. Plaintive songs such as “Home Sweet Home,” and “Auld Lang Syne” were deemed likely to incite desertion and were banned.[3]

Perhaps there were some present who remembered the dark days of 1862 and the banning of the song that winter. For them, and really for all, the rendition on April 9 must have been especially powerful. What had once been a sentimental song of parting between friends now became a requiem for the war itself and for the countless lives it had shattered.

As the music played, they may have thought of their fallen comrades, of friends left behind in shallow graves on battlefields stretching from Antietam to Gettysburg to Petersburg. Some may have thought of home, finally within reach after years of separation. Others, still numb from the long grind of war, perhaps thought only of the enormity of the moment.

As the final notes faded, the men returned to their duties, their thoughts lingering on the meaning of it all. The war that had defined their lives for years was finally over, and the music had said what words could not. “Auld Lang Syne” was not just a farewell to the past, it was a hesitant, hopeful step toward the future.

And so, its perhaps not surprising that in the years and decades after the war, “Auld Lang Syne” became a standard song at regimental reunions, at monument dedication ceremonies, and at meetings of the Grand Army of the Republic. For the veterans, singing this song was a way to honor their fallen comrades, recall the hardships and triumphs they had shared, and acknowledge the passage of time.

As the years went on, I think it also came to embody a more forward-looking spirit. The song, after all, acknowledges that while the past should be remembered, life continues. A member of Massachusetts GAR Post 68 in Dorchester composed new lyrics for his comrades to sing at their meetings, reflecting on their shared days on the battlefield. The lyrics emphasized that those days were now behind them, living on only in the pages of history, and reminded them of their present duty: to uphold charity and loyalty to one another. The song carried both the weight of remembrance and the resolve to face the future with hope and determination.[4]

[1] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, volume II (New York: Charles Webster and Co., 1886), 496.

[2] E. M. Woodward, History of the One Hundred Ninety Eighth Pennsylvania Volunteers (Trenton, NJ: MacCrellish and Quigley, 1884), 58. Woodward notes only that “one of our bands” struck up “Auld Lang Syne.” Members of the 198th Pennsylvania regimental band later asserted that it was them…but this was documented much later, as in the 1921 newspaper article, “Band 62 Years Old, Hazleton Organization Marks Anniversary—Played at Appomattox,” The Philadelphia Enquirer, October 19, 1921, 2. In this article and others like it, members of the organization, which still included two who were at Appomattox, asserts that they played as Lee rode off. Military records show that Justus Altmiller was indeed a member of the regimental band. His story of playing his cornet at Appomattox became family tradition and the cornet survived to be passed down through his family (and does indeed match an instrument he is shown holding in a wartime photograph). See National Park Service, “Justus Altimiller: Days of Auld Lang Syne—A Lesson Plan.” Admittedly, exactly who began playing at this important moment is a little murky, but the version I’ve here depicted has, I believe, a solid basis in both record and tradition.

[3] Francis Lord, They Fought for the Union (New York: Bonanza Books, 1988), 224.

[4] The lyrics by veteran James Beals were quoted in John Anderson, The Fifty Seventh Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion (Boston: E. B. Stillings & Co., 1896), 414.