The Christmas tree, now a quintessential holiday symbol, was largely unknown in New England until the late 19th century. Given my interest in Massachusetts history, I wondered: what is the earliest documented Christmas tree in the Bay State? Surprisingly, the story connects to an individual I had encountered before in a very different context.

I think we all have read that the Christmas tree as we know it originated in Germany, where it had been a cherished tradition for centuries. Decorated evergreens symbolized life and renewal in the depths of winter, and the custom of adorning them with candles, fruit, and ornaments became a central feature of German Christmas celebrations going back to Medieval times. As German immigrants arrived in colonial America, they brought their customs with them, including the Christmas tree.

There are many claims related to the “first” Christmas tree in America—all of them, it seems, contested. Windsor Locks, Connecticut, is one notable contender. The town placed a historic marker recently, proclaiming it the site of the first Christmas tree in New England. According to local lore, Hendrick Roddemore, a Hessian soldier captured during the Revolution, set up a Christmas tree there in 1777. However, historians argue there is no contemporary evidence, with the earliest account dating only to 1955.[1]

Stephen Nissenbaum, a leading historian of Christmas traditions in America, challenges the idea that these traditions emerged mostly “from the bottom up,” as with German immigrants like the Hessian soldier. Instead, he argues for “top down” origins. In The Battle for Christmas, Nissenbaum explains how Christmas transformed from a raucous, carnival-like celebration into a domestic, family-centered holiday in 19th-century America. Elites played a key role, adapting German and English customs to promote middle-class values and consumerism. (While Queen Victoria also influenced this shift, that’s not my focus here.)[2]

This dynamic resonates with my own research, and one memory stands out vividly. It’s hard to look at a Christmas tree without recalling a letter I came across years ago while studying William Smith Clark—an agriculturalist, Civil War colonel, and founder of both UMass Amherst and Hokkaido University in Japan. He’s a figure who continues to inspire me and has been the subject of several articles on this blog.

In 1850, while pursuing his doctorate in Göttingen, Clark and an American friend were boarding with a German family. On Christmas morning, they were awakened by the family’s jubilant cries of “Kaffee!” and witnessed an astonishing sight: a five-foot Christmas tree in their room, adorned with candles, sugar figures, cakes, sausages, and, Clark wrote, “all the thousand and one things that please children.”[3] Clark wrote that it was far better than the humble New England tradition of stockings by the fireplace. I find it interesting that as late as 1850, he had never seen a Christmas tree.

So, while Nissenbaum touches on it, I would more strongly emphasize the role of exchanges between German and American scholars in the 19th century in bringing the tradition over. So many New England writers, theologians, and scientists traveled to Germany to study at its prestigious universities. Germany was a hub of intellectual advancement at the time, attracting many bright minds from abroad. These scholars were exposed to the German tradition of Christmas trees, and upon their return, they shared their admiration for the practice, helping to popularize it among New England’s academic and cultural elite.

And so we come to Charles Follen, a German academic, who arrived in Massachusetts in 1824, fleeing political persecution in Europe for his radical advocacy of democracy and social reform. Settling in Cambridge, he became a Harvard professor of literature and German language and a staunch abolitionist, dedicating his life to ending slavery. His radical politics eventually led Harvard to reduce his teaching role, prompting his resignation.[4]

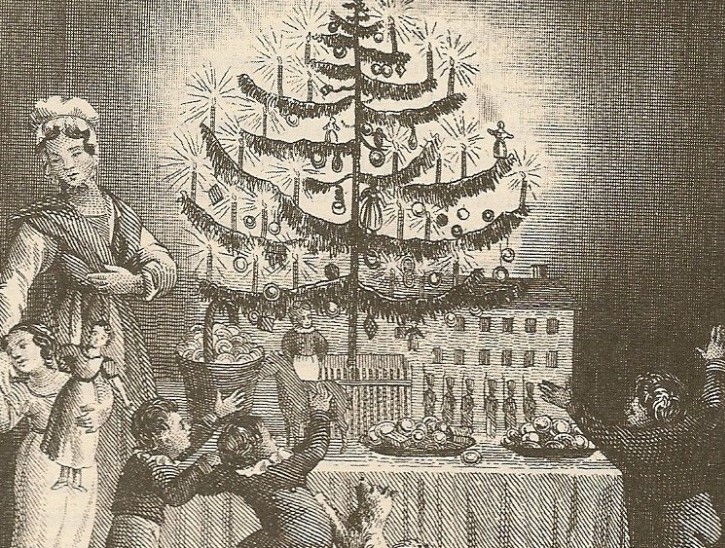

Follen is widely credited with introducing the first Christmas tree in Massachusetts in 1832 (though some claim it was the first in the U.S., this is likely not the case). His tradition was first documented by an English guest, Harriet Martineau, who published an account of her travels in America in 1838. According to Martineau, Follen set up the tree behind closed doors in a drawing room to surprise his young son and his friends during a Christmas party. When the door was opened and the blazing tree revealed, Martineau wrote, “The children poured in, but in a moment, every voice was hushed. Their faces were upturned to the blaze, all eyes wide open all lips parted, all steps arrested….At last a quick pair of eyes discovered that it bore something eatable, and from that moment, the babble began again.”[5]

According to a biography of Follen written by his wife, he delighted in this annual tradition of setting up a tree for the children at their Christmas parties. She wrote that upon the reveal, he would position himself where he could see the children’s faces. “It was in their eyes, he used to say, that he loved best to see the Christmas tree.”[6]

That Christmas of 1835 was a bright moment in an otherwise dark season in Massachusetts. As noted earlier, I had encountered Charles Follen before but not in the context of Christmas trees. Follen was one of the many abolitionists who, during the winter of 1835–1836, rallied to resist a Massachusetts legislative effort to criminalize speech on the subject of antislavery.

It was a fearful time. A few months earlier, in October 1835, an anti-abolitionist mob attacked a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and nearly lynched William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. Many of these anti-abolitionists were wealthy manufacturers who depended on southern cotton. Others believed that the South would almost certainly secede if the abolitionists continued to “throw firebrands.” They felt that by silencing abolitionists, they were saving the Union.

Amid this tense atmosphere, the Massachusetts Legislature considered a bill imposing criminal penalties on those who publicly advocated for abolition. The matter was referred to a committee, and in response, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society assembled a group to argue against the bill, including Charles Follen.

Just months after illuminating the Christmas tree described by Harriet Martineau—a symbol of hope and the best virtues of humanity—Follen stood before the legislative committee to confront the darkest forms of intolerance.

In a paper I published, I recounted this dramatic episode in detail. To summarize: Follen’s remarks at the proceedings were fearless and unyielding. He repeatedly infuriated the committee chairman, Senator George Lunt of Newburyport, by drawing a direct connection between the anti-abolitionist legislators and the violent mobs threatening abolitionists’ lives. Lunt, unwilling to hear such accusations, repeatedly interrupted Follen, ordering him to sit down and remain silent.

Undeterred, Follen pressed on. At last, he declared: “If I have not the freedom of speech” to condemn “reckless men” who “sanction mobs to assail us, then I have nothing more to say.”[7] Seething, Lunt abruptly adjourned the proceedings. The bill failed.

The Christmas tree invites us to reflect on the past, present, and future. In its journey from the forests of Germany to the drawing rooms of New England, the Christmas tree stands for more than just a festive decoration. It reflects the resilience of those like Charles Follen who championed justice and compassion even in the darkest times. The Christmas tree reminds us that the traditions we cherish today are deeply rooted in stories of courage, hope, and the enduring human capacity to find light in the face of adversity.

[1] See, in particular, Melvin Montemerlo, Windsor Locks History, Volume III (Published by the author, 2020), which convincingly debunks the whole matter.

[2] Stephen Nissenbaum, The Battle for Christmas (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1996), 177.

[3] I read the original letter in the archives of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The episode is also referenced in John Maki, A Yankee in Hokkaido: The Life of William Smith Clark (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2002), 40.

[4] Thomas Hansen, “Charles Follen: Brief Life of a Vigorous Reformer, 1796-1840,” Harvard Magazine, September – October 2002, 38.

[5] Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, vol. II (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), 179.

[6] Eliza Cabot Follen, Life of Charles Follen (Boston: Thomas Webb & Co., 1844), 255.

[7] Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, and Massachusetts, An account of the interviews which took place on the fourth and eighth of March between a committee of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, and the committee of the Legislature, (Boston: Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, 1836), 19.