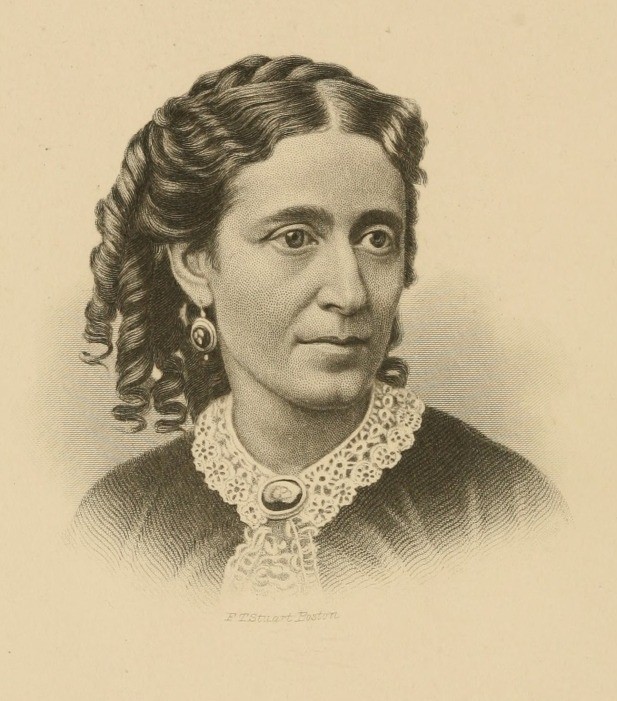

Few, even in her hometown of Plymouth, Massachusetts, know of Lizzie Doten. And yet in her day, she rose to celebrity as a leader of the Spiritualist movement, speaking to crowds of thousands in cities across the country. She led a remarkable life, left behind an amazing body of work in her poems, and was all the more noteworthy for a turn she made towards politics during the Civil War.

Born in Plymouth in 1827, a descendant of Pilgrim families, Lizzie Doten dedicated much of her life to exploring the boundaries between this world and the spiritual realm. She firmly believed in the ability of souls to communicate with “invisible beings.” She claimed she received direct communications from the spirits of the dead, particularly through poetic inspiration.

This “gift,” she wrote, began to reveal itself to her at a very young age. In the introduction to one of her volumes of poetry, Poems from the Inner Life, Doten describes sitting by the fireside as a child during long winter nights with her face and head enveloped in her apron to block out external sight and sound so that she could focus on “inner” voices. She said she honed her ability to hear these voices as a young woman by lying in a darkened closet for hours at a time, carefully listening, struggling as the “waves of the mysterious Infinite…rolled in a stormy flood over me.” Through prayers and tears, she said, she learned to attune herself to higher spiritual truths.[1]

Doten’s “natural poetic tendencies,” as she described them, attracted kindred spirits from beyond, who could “cast their characteristic inspirations” upon her.[2] For Doten, poetry was not just an art form but a spiritual practice, a medium through which the voices of the dead could speak and reveal their truths. She claimed to commune with William Shakespeare, a force of such brilliance, she said, that his influence “seemed to overwhelm and crush me” and she “shrank from it” and could receive only two poems from him. She was also “given” poems, from Robert Burns, a far more “easy” and “cheerful” presence, she alleged.

But the most important and mysterious of her influences, according to Doten, was none other than Edgar Allan Poe. She wrote:

The influence of Poe was neither pleasant nor easy. I can only describe it as a species of mental intoxication. I was tortured with a feeling of great restlessness and irritability, and strange, images crowded my brain. Some were as bewildering and dazzling as the sun, others dark and repulsive. Under his influence, particularly, I suffered the greatest exhaustion of vital energy, so much so, that after giving one of his poems, I was usually quite ill for several days.[3]

Towards the end of one lecture in Boston, she went into a trance and recited a poem from Poe. A skeptical newspaper reporter wrote that she surely was “incapable” of writing such a poem herself and that she may have memorized a work written for her by someone intimately familiar with Poe’s style and “intensity of feeling.” And yet, the reporter conceded, “if Miss Doten is honest, and the poem originated as she said it did, it is unquestionably the most astonishing thing that Spiritualism has produced.”[4] Her poem entitled “The Streets of Baltimore” is an uncanny imagining of Poe’s tortured last days but also his redemption in the afterlife, all of it “given” to her from his ghost.

Of course, the Victorian era was a time when the supernatural was more than just a curiosity; it was a way of understanding the mysteries of life and death. Fueled by the zeal of religious revival transforming the nation at that time, Spiritualism attracted an enormous following in the 1850s. Just as it began to ebb, the movement was rekindled by the Civil War. With the immense loss of life during the war, millions of Americans were left grieving. Families wanted reassurance that their sons, brothers, and husbands had found peace in the afterlife, and many turned to Spiritualist practices to find that comfort.

And so the fame of Lizzie Doten, and other Spiritualists, only increased. It was during the war, however, that Doten made a fascinating pivot. Her lectures and writings took a political turn. She began to advocate for the cause of emancipation and the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln. Doten feared that the hard-won gains of freedom embodied in the Emancipation Proclamation would be reversed if Lincoln were not reelected in 1864. She warned of the moral reckoning that would come for oppressors who denied freedom, drawing on imagery of natural convulsions–earthquakes and storms–to underscore the unstoppable force of justice.

Given her celebrity, and the large crowds to which she spoke, Doten was arguably one of the most prominent female political speakers of the time. During one remarkable speech in Philadelphia, she framed the fight for emancipation as one in which the dead, particularly the fallen soldiers “who in agony had left their bodies upon the battlefield”, were spiritually present, watching to ensure that the living carried out the work of justice they had died for.[5]

Doten also spoke on behalf of women, particularly those displaced by the war who had been forced to seek employment outside the domestic sphere. She advocated for the labor rights of women, recognizing that the war had reshaped the economy and that women’s contributions should be supported and valued.

Doten was unapologetic for her convictions, whether political or spiritual. She did not try to persuade skeptics. She acknowledged that her claims would be met with disbelief. Her views, in keeping with the core principles of the Spiritualist movement, were deeply personal. Her mediumship, poetry, and public speaking served as vehicles for expressing her conviction that death was not an end, but a transition to another state of being, where communication with those left behind remained possible.

[1] Lizzie Doten, Poems from the Inner Life (Boston: Colby & Rich, 1863), ix-x.

[2] Doten, xi.

[3] Doten,xxi-xxii.

[4] Article from the Springfield Republican quoted in Doten, Poems from the Inner Life, 104.

[5] Chicago Daily Tribune, August 12, 1864, 5.