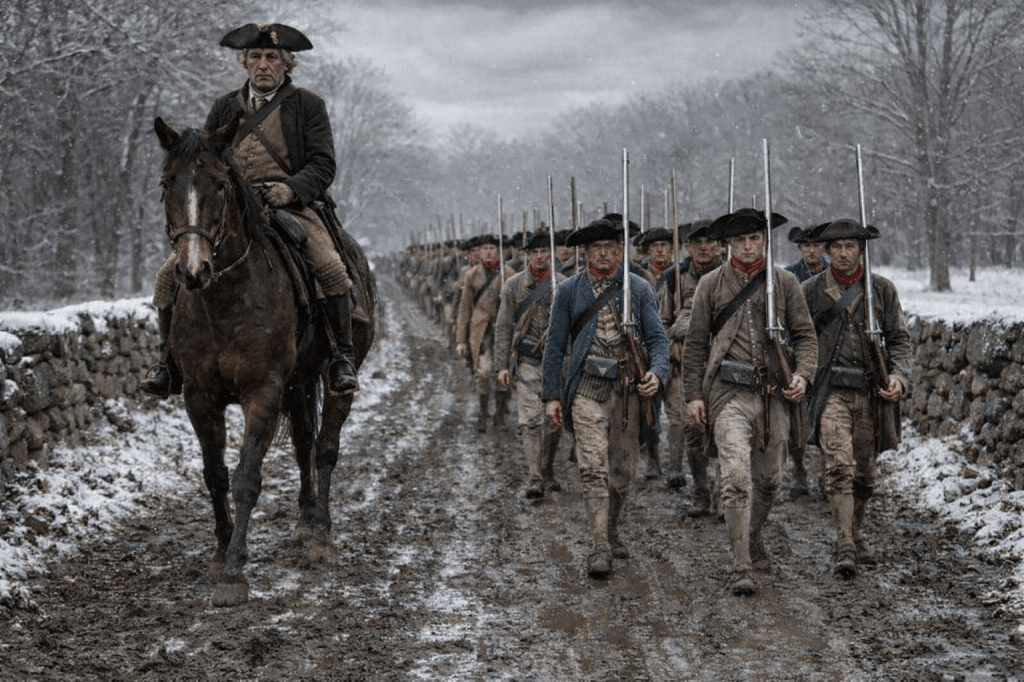

He had never seen so much mud in his life. The road into Roxbury was a brown river churned by boots and wagon wheels, and his shoes—good, workmanship from his own bench—were already soaked through and caked with earth from the road.

Ahead, the land rose in ragged ridges of earthworks, raw banks of clay and sod that seemed to wind across the farmers’ fields like a colossal snake. He spotted a cannon propped up on one of the muddy parapets, something he had never seen before, aimed out at the blue sky to the north. As they mounted the hill, he could just see over the walls. Beyond them, faint and bluish in the late spring haze, Boston lay across the Neck—a great mound of buildings packed together, steeples here and there pale against the clouds. Somewhere in that cluster of roofs, the King’s troops and loyalists waited, bottled up and angry. The Plymouth shoemaker shifted the musket on his shoulder and tried not to stare too long.

They told them this was camp. A farmhouse and some barns, fences half-stripped for firewood, leaned along the road. The barns were crowded with men and gear; cattle grazed where they could find grass between piles of stones and brush. Everywhere there was the smell of smoke, cattle, sweat, and damp wool. Men from Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury, Middleborough—some faces he knew, others he had never seen—moved in small knots through the mire, laughing, swearing, or simply silent with the weight of it all. He looked down at the mud creeping up his leggings and tried to imagine this place as home—not for a night, or a week, but for months. Through heat, through rain, through whatever winter might bring.

He thought of his shop back in Plymouth, the rhythm of awl and thread, the good, plain smell of leather. Then he looked up again at the redoubt, at the road to Boston, at the gray distance where the British held the city—and he understood, in a way he had not before, that this was an army still in the making, and he was part of it now.

This article is the second of a two-part look at the First Plymouth County Regiment during the opening year of the American Revolution. Two hundred and fifty years ago, on December 31, 1775, Colonel Theophilus Cotton’s Plymouth regiment quietly disbanded. This anniversary seems an appropriate moment to pause and review what their service that year looked like. In Part One, I focused on the “where” and the “who” of the regiment. In this Part Two, I turn to the “what” and the “how.” Here, the emphasis is on experience: what it was like to live for months in a makeshift military camp at Roxbury; how Cotton’s men labored on the fortifications that guarded Boston Neck; and how, gradually, a militia of neighbors began to resemble an army.

I covered the role of Colonel Cotton’s regiment during the Battle of Bunker Hill in an earlier post, but it is worth summarizing here—especially because what happened at Roxbury on June 17, 1775 helps us understand what daily life was like for the Plymouth men, caught between routine camp duty and very real danger.

When news spread through the American lines on June 17, 1775, that the British were attacking the newly built fortifications on Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill in Charlestown, the Roxbury sector braced for action. Though they were quite some distance from the fighting, General John Thomas, commanding at Roxbury, was rightly convinced that the British might attempt a diversionary thrust at Boston Neck to break the siege from the south. If the Neck were forced, the British would once again control the only land route between Boston and the mainland.

Cotton’s regiment, positioned close behind the Roxbury gate and fortifications, was therefore among the regiments placed on alert. Men stood to arms. The artillery batteries near the Neck opened fire toward the British positions, both to harass them and to discourage any movement in that direction. Contemporary accounts recall a heavy and sustained cannonade launched from the American lines at Roxbury that day—one participant recalled the fire as “warm work,” the air filled with smoke and the crash of returning British shot arcing toward the earthworks and the town behind them.[1]

British guns in Boston and on the Neck answered the American fire. Roxbury, once a quiet village, became, for much of the day, a battered forward camp. Round shot tore through abandoned houses already riddled from earlier skirmishing. American officers repeatedly called the men to alert, expecting at any moment to see British regulars advancing across the narrow causeway into the teeth of the Roxbury redoubt.[2]

The British infantry attack never came. The blow fell, as we know, almost entirely on Breed’s Hill. When the fighting ended and the British held the Charlestown peninsula at terrible cost, the Plymouth men at Roxbury remained in place. They would spend the rest of the year guarding the same muddy fields, the same fragile ramparts, under the same guns.[3]

If the Battle of Bunker Hill showed Cotton’s men the terror and noise of war, the regiment’s orderly books reveal something much more familiar to soldiers in every age: boredom, discipline, and the daily struggle to keep an army together.

One of the most memorable entries is also one of the most human. The regiment was warned that no man was to throw rocks at the farmhouse (where presumably the officers were quartered). We are not told who the targets were, or what offense the rocks were thought to answer. Perhaps it was idle mischievousness; perhaps a crude contest of arms; perhaps simply young men with too much time and too many stones at hand. But the irritation of the officers is palpable. A New England army was being formed—and it would not, the adjutant seems to say, be built on rock-throwing.[4]

Other entries strike a sterner tone. Sabbath observance was expected and enforced. Men were instructed to behave with “decency” on the Lord’s Day, and to avoid unnecessary noise or disorder.[5] Cleanliness—of person, clothing, and campsite—received repeated attention. Officers were ordered to see that their men kept themselves and their quarters as clean as circumstances allowed. Dirt, slovenliness, and disorder were not simply unpleasant; they were military liabilities in a densely packed camp where sickness could sweep through ranks already weakened by fatigue and poor rations.

The regiment’s duties were those of a siege army. Men were posted to the Main Guard near the Boston Neck gate, to outlying sentry posts, and to the “hill above the mills”—a vantage point overlooking the Stony Brook mill sites. Details were regularly assigned to fatigue work: digging, hauling brush and fascines, repairing parapets damaged by weather or British artillery, and cutting wood. Curfew and leave were closely regulated. Men were not to wander far from camp; if they went into the countryside without leave, and especially if they failed to return on time, they risked punishment.[6]

Another thread running through the orderly book is the steady rhythm of courts-martial. It is a clear sign that this was no longer a loose gathering of militia, but an army under enforceable law. Men were frequently ordered to appear before regimental or brigade courts to answer charges ranging from absence without leave, neglect of duty, drunkenness, and disobedience, to the loss or abuse of public arms and equipment.[7] Punishments varied according to the offense and the judgment of the officers, but the mere fact of formal trial, with accusations recorded, witnesses summoned, and sentences entered, shows a regiment steadily internalizing military procedure.

The “Articles of War,” adopted by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in the spring and echoing British practice, gave legal framework to these proceedings, and the adjutant’s neat entries remind us that discipline in the Roxbury lines was not theoretical.[8] Order had to be maintained among hundreds of men crowded into muddy quarters under the guns of Boston, and the courts-martial, alongside roll calls, passes, and inspections, became a key instrument in forging that order.

As Christmas 1775 arrived, for the New Englanders at Roxbury, who largely did not observe Christmas as a religious feast, the day likely differed little from any other. Just a continuance of biting cold, the shortness of daylight, and the knowledge that their enlistments were about to expire. The Plymouth men probably stood guard as usual, cut wood, tended fires, tried to keep their muskets dry, and spoke about home. Some must have been already counting the days.

On December 31, 1775, the First Plymouth County Regiment ceased to exist (at least in its present iteration). The men’s enlistments expired, and, as General Washington would lament more than once, the New England army temporarily thinned as regiments disbanded and re-formed.[9] There was no grand farewell. The men of Plymouth County shouldered their packs and walked south toward the roads and villages they knew.

They would not soon forget the army they left behind—the one they had played a part in shaping. If the orderly book sometimes reads like a schoolmaster’s scold—no throwing stones, keep clean, be back on time—it also marks the slow, deliberate transition of New England militia into a disciplined fighting force. And the men of Colonel Cotton’s Plymouth County Regiment stood that long watch at Roxbury as part of that transformation. And, for many of them, it was only the beginning of their service. They would be back in the ranks soon enough with other units…

[1] Richard Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston (Boston: Little, Brown, 1849), 188–192.

[2] Ibid., 190–193; Jeremy Belknap, quoted in The Belknap Papers, vol. 2 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1854), 21–23.

[3] Allen French, The First Year of the American Revolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1934), 248–254.

[4] Adjutant Joshua Thomas, “Orderly Book of Col. Theophilus Cotton’s Regiment,” June 22–July 17, 1775, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Journal of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, 1774–1775 (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1838), 510–518, containing the adopted Articles of War.

[9] George Washington to Joseph Reed, January 14, 1776, in The Writings of George Washington, ed. Jared Sparks, vol. 3 (Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1835), 188–190.