At 1 a.m. on April 19, 1861, the men of the 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia were asleep on the floors of the Girard House Hotel in Philadelphia when the long roll sounded. Coincidentally, it was about the same time that the alarm bell had been rung in Concord, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775 warning of the advance of British Regulars.

The 6th Massachusetts was largely made up of men from Middlesex County and among them were descendants of those who had fought in Concord, Lexington and along the Battle Road at the start of the Revolution. Company E, the “Davis Guards” from Acton, was named after Capt. Isaac Davis, the minuteman captain who, at the head of his company, led the advance on the Old North Bridge and became the first officer killed in the Revolution.

These “Minutemen of ’61,” waking up in Philadelphia after very little sleep, were weary from three days of excitement and exertion. On the night of April 15, following Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers, orders went out the various companies of the 6th Massachusetts to muster at the regiment’s headquarters in Lowell. The next morning, April 16, rain and sleet fell as the eight companies boarded a train for Boston. They were welcomed by enormous crowds and quartered in Boylston and Faneuil Halls for the night. On April 17, they were issued rifled muskets. Three additional companies were attached to the old militia regiment to fill out their numbers, making eleven companies in all. Governor John Andrew presented them with colors saying, “You carry with you our utmost faith and confidence.”[1]

The same day, they boarded a train for New York and were received with even larger crowds. At noon on April 18, they departed by train for Philadelphia where the cheering throng was so thick they had to move through the streets by the flank, in fours, rather than by column of companies. The whole journey, wrote a historian of the regiment, was, “one grand ovation, such as no regiment had ever received.”[2]

The journey ahead of them on April 19 would be starkly different.

The commanding officer of the regiment was Colonel Edward F. Jones (1828-1913), a 32 year-old merchant who resided in the small mill town of Pepperell, Massachusetts. He had been a part of the Massachusetts militia since 1854 and became colonel of the 6th Massachusetts in January 1861. In that capacity, he was the first militia commander to issue report of readiness in response to the Governor’s January 1861 orders.[3]

While his men were asleep in Philadelphia, Col. Jones had a grave conversation with General P.S. Davis of the Massachusetts militia regarding the state of things in Baltimore, through which the regiment would pass on April 19 on their way to Washington. Baltimore had long since been given the nickname “Mob Town.” Indications were that it would live up to its reputation. Secessionist sentiment was widespread there. And even moderate citizens were infuriated by the notion of their city becoming the gateway for an invasion of Southern States. The 6th Massachusetts would likely have to confront a violent reception.

It was for this reason that Col. Jones woke his men in the middle of the night on April 19 in hopes of reaching Baltimore earlier than expected and perhaps passing through the city before a mob could assemble. About the time the rank and file were woken, Col. Jones and Gen. Davis consulted with the president of the Philadelphia & Baltimore Railroad, Samuel Morse Felton, a transplanted Bay Stater and native of Saugus, Massachusetts.

Jones’s chief concern was not the mobs in Baltimore (which might result in a few casualties) but the possibility of a sabotaged track which could derail the train resulting in the slaughter of virtually the entire regiment. Felton made arrangements to have a pilot engine precede the train in which the 6th Massachusetts rode. It must have been a terribly anxious ride in that pilot engine.[4]

Soon after they left Philadelphia, Col. Jones gave the order to distribute 20 rounds of ammunition along with an order to his men which read, in part:

…You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and perhaps assaulted, to which you must pay no attention whatever, but march with your faces square to the front…even if they throw stones, bricks, or other missiles; but if you are fired upon and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire. Do not fire into any promiscuous crowds, but select any man whom you may see aiming at you, and be sure you drop him.[5]

At every train station along the approximately 100 mile route to Baltimore, railroad officials communicated by telegraph with their counterparts in Baltimore and were assured that things were quiet in the city.[6] They did not communicate their progress or estimated arrival time to city officials or police until they were a half hour outside the city, a fact which Baltimore Mayor George W. Brown would later call a blunder. [7] The police, the mayor felt, could have quelled the mob before it grew out of control, thereby diminishing the bloodshed. It might be inferred that the railroad officials trusted their own employees more than the Baltimore police to keep secret the estimated arrival of the train.

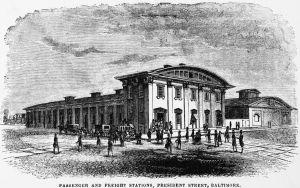

The President Street Depot, Baltimore. The front building still stands and is now the Baltimore Civil War Museum.

The train bearing the 6th Massachusetts arrived at Baltimore’s President Street Station around 10 a.m. The train, more than thirty cars, also transported a Pennsylvania regiment which had not yet been issued uniforms or muskets. For that reason, the Pennsylvania regiment would not make any attempt to get through Baltimore and instead returned to Philadelphia before the day was done.

As evidenced by his order, Col. Jones apparently expected to disembark his entire regiment and march to the Camden Street Station (about 1.2 miles distance primarily along Pratt Street and the Baltimore waterfront) where they would board a train to Washington. Jones was not aware of the local practice of uncoupling train cars and drawing them individually by horse power along street rails from one station to another. Before he knew what was happening, horse teams had been hitched and the cars were making their way to Camden Station.[8] This, Mayor Brown later wrote, was another major part of the “blunder.” If the regiment had originally set out on foot through the city, they might have passed through quickly and without drastic incident.

The first several cars had little difficulty making it to their destination. However, as car after car passed down Pratt Street, the inhabitants of the city began to gather and grew increasingly irate. Soon they were shouting, throwing bricks and stones. The car bearing Company K, the seventh and last company to make it through by rail, was derailed three times by small obstructions. Railroad workers along with soldiers had to get out amidst a storm of projectiles and put the car back on track.

Pistol shots soon joined flying debris and the men of Company K were forced to lie down on the floor of the car as it slowly progressed.[9] A soldier who had been shot in the thumb held the wound up to Major Benjamin F. Watson and asked if they could finally return fire. Major Watson gave the order and men fired out the windows of the car. Company K made it through to Camden Station. The cars behind them, bearing four more companies, did not.

Before the chaos had gotten underway, Mayor George Brown was in his law office when some of the city councilmen informed him that the troops were about to arrive. He quickly went to Camden Station to await their arrival. There he found the city police, led by Police Marshall George Proctor Kane, dealing with an angry crowd. Eventually, cars bearing seven of the eleven companies arrived at Camden Station. Mayor Brown noted that the windows of the last car were “badly broken.”[10]

About this time, also at Camden Station, Col. Jones, who had been in one of the lead cars, was informed by a railroad official that the railway on Pratt Street had been obstructed and that four companies could not get through.

Thomas Garrett, President of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, approached Col. Jones and informed him, “Your soldiers are firing upon people in the streets.”

“Then,” answered Jones, “they have been fired upon first.”

“No, they have not,” Garrett responded.

“My men are disciplined,” Jones said, “my orders were strict, and I believe they have been implicitly obeyed.”[11]

Unaware of this exchange, Mayor Brown also heard of the obstruction on Pratt Street and ordered Marshall Kane to lead his police force in that direction. Brown set out in advance on foot by himself.[12]

A formidable obstruction had indeed been thrown down by the crowds near the head of Smith’s Wharf, at the corner of Pratt and Gay Streets, about a third of the way along the route between the two stations. Seventeen year-old George Wilson Booth, a member of the Maryland militia who would later become a Confederate soldier, made his way to Pratt Street around noon, curious about all the noise.

Booth would later write that he cherished the Union, and did not care about slavery one way or the other, but, “when it became apparent, without question, that the hope of state action was impracticable, by the reason of this military occupation, then, without hesitation, I chose to caste my fortune with the south…”[13] At the time of the Baltimore Riot, that decision still lay in the future for Booth, but what he witnessed on April 19 set him on his course.

When young Booth reached Pratt Street, he saw that the tracks had been barricaded by several cart loads of sand along with anchors and chains dragged by the mob from the wharves. Several horse drawn train cars were stopped by the obstruction and as Booth watched, the horse teams were moved from the front to the rear of the cars and the remainder of the 6th Massachusetts was slowly drawn back to President Street Station. “The soldiers in the cars,” Booth later recalled, “were subjected to the most violent abuse.” Much worse was yet to come.

As the cars returned to President Street Station, it was clear to Captain Albert S. Follansbee, commanding Company C from Lowell, that they had a difficult march to make. The other three company commanders agreed to defer to him, giving him command of the detachment. The four companies numbered 220 men. They were about to face a crowd estimated at 10,000.

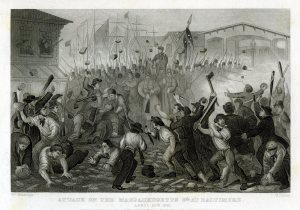

Capt. Follansbee ordered the battalion to form in the street. He gave the command to wheel into a column of sections. With the command, “Forward, march!” the formation stepped off. And the moment they did so, the projectiles started to fly. Bricks, stones, shouts, taunts. Captain Follansbee recalled that one man shouted that they would, “kill every ‘white nigger’ of us before we could reach the other depot.”[14]

Capt. Follansbee ordered the battalion to form in the street. He gave the command to wheel into a column of sections. With the command, “Forward, march!” the formation stepped off. And the moment they did so, the projectiles started to fly. Bricks, stones, shouts, taunts. Captain Follansbee recalled that one man shouted that they would, “kill every ‘white nigger’ of us before we could reach the other depot.”[14]

About 500 yards into the march, they reached the left turn onto Pratt Street and a small wooden bridge. The crowds had torn up most of the planks and, as Capt. Follansbee put it, the soldiers had to play “scotch hop” to get across along the bare wooden frame. The majority of the crowd was behind them and as the regiment struggled over the bridge and a small barricade on the other side of the bridge, Follansbee saw an opportunity to put some distance between his men and the bulk of the mob. Knowing that the crowd would also have to clamber over the vandalized bridge, Follansbee gave the order to double-quick. It turned out to be a bad move.

The soldiers’ rapid pace only roused the crowd all the more—the inhabitants construed it as a sign of panic. The projectiles intensified. Shots were fired from stores and houses surrounding them. Capt. Follansbee ordered his men, as he later put it, “to protect themselves.” The soldiers fired back, at will. There was no organized volley firing.[15]

Mayor Brown, meanwhile, had reached the obstruction at the intersection of Gay Street. He ordered it removed and some policemen and citizens obeyed. He then walked further east on Pratt Street and soon saw and heard the approach of the battalion. “They were firing wildly,” Mayor Brown recalled, “sometimes backward, over their shoulders. So rapid was the march that they could not stop to take aim. The mob, which was not very large, as it seemed to me, was pursuing with shouts and stones, and, I think, an occasional pistol-shot. The uproar was furious.”[16]

Brown met the head of the column and shook hands with Captain Follansbee, saying, “I am the Mayor of Baltimore.” Follansbee introduced himself. Brown immediately recommended to Follansbee that they cease the double-quick, knowing that it only added to the furor. Follansbee agreed and gave the order to slow the column. They now marched at a deliberate pace.

Noting that the majority of the mob was behind them, Brown considered recommending that the rear section face about and fire a volley. He later wrote, “Once before in my life I had taken part in opposing a formidable riot, and had learned by experience that the safety and most humane manner of quelling a mob is to meet it at the beginning with armed resistance.” [17] Despite his instinct that a heavy hand was needed, Brown concluded it was not his place to tell Follansbee what to do. The formation moved on, receiving punishing abuse, and firing in all directions as threats appeared.

At about this time, Private Luther Ladd, a seventeen year-old mechanic from Lowell, was just making his way across the remains of the Pratt Street Bridge, being near the rear of the column. As he did so, a civilian hurled a piece of heavy scrap iron from one of the roof tops and it stuck Ladd in the head. He staggered for a moment. One of the rioters rushed forward, grabbed Ladd’s musket from him, and shot him in the leg with the round Ladd had loaded himself.[18] Ladd died on Pratt Street. Some weeks later, Harpers Weekly would publish a likeness of him, proclaiming Ladd “the first victim of the war.”[19]

Up towards the head of the column, young George Booth was still in the crowd, now watching the 6th Massachusetts march through the gauntlet of violence. “I was standing at the corner of Commerce street and the troops were at the moment passing that point, when a soldier, struck by a stone, fell almost at my feet, and as he fell, dropped his musket, which was immediately seized by a citizen, who raised it to his shoulder and fired into the column.” After firing, the man who picked up the musket turned to Booth and asked if he had any cartridges. As it happened, Booth had two, having left them in his pocket, he wrote, after coming off militia guard duty the previous night. He gave them over and showed the man how to reload.[20]

For several blocks this violence continued until a force of roughly 50 police officers under the command of Marshall Kane arrived. Mayor Brown ordered them to the rear of the column where the bloodshed was at its worst.

…Throwing themselves in the rear of the troops, they formed a line in front of the mob, and with drawn revolvers kept it back…Marshall Kane’s voice shouted, ‘Keep back, men, or I shoot!’ This movement, which I saw myself, was gallantly executed, and was perfectly successful. The mob recoiled like water from a rock…This nearly ended the fight, and the column passed on under the protection of the police, without serious molestation, to Camden Station.[21]

Marshall George P. Kane, who placed himself and his fellow police officers between the mob and the Massachusetts soldiers, had strong secessionist sympathies and would later resist increasing Federal occupation of Baltimore. He would be arrested for sedition by Federal authorities who moved him about to several Army prisons, including Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. After his release in 1862, he became an operative for the Confederacy in Canada.[22]

Mayor Brown, after leading the column by the side of Capt. Follansbee for several blocks, eventually decided that he was in the “wrong place” and sought safety. Capt. Follansbee later alleged that he had seen Mayor Brown pick up a soldier’s fallen musket and fire it into the crowd. This was vehemently denied by Brown in his published account of the riot.[23]

The four companies rejoined the rest of their regiment at Camden Station, leaving behind them four killed. 36 had been wounded. There were 12 civilians killed and an unknown number of wounded.[24]

With his regiment reassembled, Col. Jones knew it was essential that they leave the city as soon as possible. Fury was dangerously high on both sides. His company officers and the rank and file wanted vengeance. And the mob was still active around Camden Station. Railroad employees informed him that citizens were attempting to tear up the track leading to Washington. They had to go quickly.

The train bristled with muskets aimed out of virtually every window. In an attempt to bring an end to the violence, Jones ordered that the blinds of the cars be lowered and his men stand down. Leaving the station slowly, the train stopped and started repeatedly, encountering many obstructions which the employees were forced to remove. Eventually, the conductor told Col. Jones it was impossible to proceed. Jones responded, likely with some intensity, “We are ticketed through, and are going in these cars. If you or the engineer cannot run the train, we have plenty of men who can. If you need protection or assistance, you shall have it; but we go through.”[25]

The 6th Massachusetts, the first troops to arrive in Washington in response to Lincoln’s call for volunteers, reached Washington late in the afternoon of April 19.

[1] John Wesley Hanson, Historical Sketch of the Old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, During Its Three Campaigns in 1861, 1862, 1863, and 1864, (1866), pp. 15-18

[2] Hanson, p. 19

[3] Hanson, p. 13

[4] Hanson, p. 22

[5] “Report of Colonel Edward F. Jones,” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, the United States War Department, Series 1, Volume 2, (1880), p. 7

[6] Hanson, p. 23

[7] George William Brown, Baltimore and the Nineteenth of April 1861: A Study of the War, Volume 3, (1887), p. 44

[8] Hanson, p. 24

[9] Hanson, p. 25

[10] Brown, p. 48

[11] Hanson, p. 27

[12] Brown, p. 49

[13] George W. Booth, Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States, 1861-1865, (1898), p. 7

[14] Hanson, p. 40

[15] Ibid.

[16] Brown, p. 49

[17] Ibid.

[18] Gene Thorp, “First Civil War Deaths Took Place in Baltimore,” A House Divided: News and Views about the 150th Anniversary of the American Civil War, a blog by the Washington Post, 4/19/2011

[19] Harpers Weekly, June 1, 1861

[20] Booth, p. 8

[21] Brown, p. 51

[22] Frank B. Marcotte, Six Days in April: Lincoln and the Union in Peril, (2005), p. 162

[23] Brown, p. 51

[24] Brown, p. 53

[25] Hanson, p. 32

March 9th, 2015 at 11:27 am

Oh heavens.

You know my love of the Old Sixth and the story of the Pratt Street Riot. I do have to ask: I note that you don’t specifically site the derangement of the 6th’s cars at Havre de Grace– I don’t have it in front of me, but I recall seeing in Hanson that Co. C, D, I and L were thought to already have been in front of K, which was why they were left behind, that on account of the derangement of the cars’ order.

…or am I depending too much on memory?

March 9th, 2015 at 12:10 pm

You’re spot on about that. I did not include it because my narrative was simply getting too long. But, yes, the derangement of cars was unexpected and certainly added to the confusion.

March 9th, 2015 at 12:58 pm

I do not believe any narrative about the Old Sixth can be too long. ((grin))

In other news, I now see the raging error of posting up comments before the third cup of coffee. Oh, the misspellings and wretched grammar. I hang my head in shame.

March 9th, 2015 at 11:28 am

Also: Splendid narrative. Just splendid.

April 27th, 2015 at 10:17 pm

[…] https://historicaldigression.com/2015/03/05/6th-massachusetts-and-the-baltimore-riot/ […]

August 3rd, 2015 at 8:20 pm

Your article very helpful. I am seeking any info re: 2lt. Darius Stevens of Co.L at the time of this event. Anything would be helpful. I am in possession of his medals and other items he returnred with from the war.

Leonard Adams, member, Company of Military Historians, and founder Fort Nathan Hale Restoration.